|

|

|

| : Reports : Under-Represented Populations |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| Annotations |

Report Excerpts |

|

| |

Excerpt 1

[University of Denver]

|

|

Quantitative

Analysis:

Describes statistical procedures

|

Dependent t-tests were conducted on the pretest/posttest

differences for each of the 11 questions on the Student

Questionnaire of SEM Knowledge and Attitudes. 15 students

completed this questionnaire at both time periods, and

given the hypothesis that student knowledge would increase

in SEM areas, one-tail tests were used (see Table 7

for t-test results).

|

|

Presents response rate statistics

|

Table 7

Dependent t-tests for the Student

Questionnaire of SEM Knowledge and Attitudes

| TIME |

GIRLS' COMPLETED SURVEY |

% |

PARENTS' COMPLETED SURVEY |

% |

| 1 |

18 |

94.7 |

19 |

100.0 |

| 2 |

11 |

57.9 |

11 |

57.9 |

| 3 |

15 |

78.9 |

14 |

73.7 |

|

|

| |

Excerpt 2

[University of Washington]

|

|

Quantitative

Analysis:

Describes procedures for data verification

|

The completed survey questionnaire forms were entered

into a personal computer using R-Base, a standard data-base

management package. Preliminary data analyses were used

to detect unusual values or patterns and logical inconsistencies.

Telephone calls to respondents were made to gather missing

answers.

|

|

Describes statistical procedures used to

organize and reduce the data

|

Statistical analysis was performed with SPSS/PC+ (Statistical

Package for Social Sciences) Version 3.0 on an IBM-compatible

personal computer. Data analyses, aimed at describing

program characteristics, consisted primarily of summary

statistics (means, medians, standard deviations, ranges,

and proportions or percents). Two-way tables and correlations

were used to describe associations between characteristics.

Statistical tests of hypothesis included Chi-Squared,

t-tests, and analysis of variance. Confirmation of t-test

and ANOVA results was done using non-parametric

procedures.

A series of t-tests was used to determine if there

were any significant relationships between variables.

The t-test was a two sample t-test for unequal variances

to test whether or not the means of the two populations

were significantly different. Significance was defined

at p<.05 to p>-.05. Since a t-test assumes the data

come from a normal distribution, the data were also

tested using a Mann-Whitney test, which is a non-parametric

test. The results of the two tests were

similar.

A total of 285 variables were included in six sections

of the survey. The six sections corresponded with the

six hypothesized underlying constructs/prerequisite

conditions for success. Variables within each of the

six sections were collapsed into a smaller set of defining

variables. At the conclusion, ten to fifteen variables

defined each construct/prerequisite

condition.

Factor analysis was then executed on each of the six

sets of variables, which defined an underlying construct,

such as commitment from the Dean. The objective was

to detect those variables and/or groups of variables

that tended to produce similar responses or response

trends and to test the hypothesis that the above mentioned

prerequisite conditions or underlying constructs would

be present among those institutions with successful

intervention programs.

Several linear combinations of variables (factors)

were chosen within each construct, because they explained

most (>60%) of the variability in the data. These sets

of factors were rotated orthogonally to find simpler

and more meaningful patterns in which each factor describes

the variation shared by a subset of the information

highly related to it, and ignores the variation in other,

less related variables. Variables were chosen as important

components in a factor when correlations between a factor

and a variable were greater than 0.5 or less

than -0.5.

|

|

| |

Excerpt 3

[Girls Inc. of Alameda County]

|

| |

Evaluation Results:

The following section presents the results

of the Eureka evaluation process. It includes a profile

of Eureka participants and data obtained from the participant

assessment, focus group meeting, interviews with parents

of Eureka graduates and interviews with former Eureka

participants.

|

|

Quantitative

Analysis:

Presents mean response on satisfaction scale

|

Eureka graduates were asked to rate the

overall Eureka Teen Achievement Program on a scale from

1-low to 5-high. Graduates rated the program an overall

4.05.

|

|

Qualitative

Analysis:

Presents responses to open-ended questions

|

During the focus group meeting participants

relayed examples of ways in which the Eureka program

gave them confidence to take on risks or new challenges

both in school and in other parts of their lives. A

request for specific examples of risks or challenges

that they would not have taken had it not been for Eureka

elicited these responses:

"I think it (Eureka) gives you confidence,

more confidence in going out there and knowing its okay

to try your best and that you can

succeed."

"They (Eureka) tell you you have to take

a risk in life, you know. They tell you … you are a

beautiful person and you can only do what you can … It's

all about who you are inside and what other people think

about you just doesn't matter, and they give you that

kind of confidence and you're just like, oh goodness,

I can do this or you know if I don't do it this time

I can still strive for it next time

…"

"They push you to make goals for yourself

and set those goals, and then when you reach those goals

you make other ones, and you just continue on to new

goals."

"Running for office … if you don't have

the confidence within yourself that Eureka can help

you get, you will not succeed at … High School as Vice

President of the Senate … we had an assembly on Friday

and I said "Hi everybody, I'm … Vice President of the

Senate." I got the loudest yells of anyone, you know

what I'm saying? This is the confidence the Eureka has

given me."

|

|

| |

Excerpt 4

[Purdue University]

|

| |

*Graduate Mentoring

Program—Engineering: 1994-1997

The Graduate Mentoring Program in Engineering

from 1994-1997 has consisted of 190 students. A list

of topics, speakers, and an example of formative evaluations

utilized throughout the year at monthly meetings for

M.S. and Ph.D. women engineering students are included.

The one page evaluation sheets contained items that

dealt with the number and nature of informal contacts

between Mentees and Mentors as well as an assessment

of whether monthly events were addressing participants'

needs for support, self-esteem, and strategies. Sheets

were distributed to attendees at the close of meetings,

and findings were used to assess program goals and make

program improvements. Table 9 contains group means for

each of the monthly meetings held from 1994-1997 as

well as overall group means related to specific goals

of the program (providing support, heightening self-esteem,

and sharing strategies). Responses of participants were

on a 5 point Likert scale that ranged from strongly

agree (5.0) or agree (4.0) to strongly disagree

(1.0).

|

|

Quantitative

Analysis:

Summarizes survey results in table form

|

Table 9. Graduate Mentoring

Program—Monthly Meetings—Group

Means, 1994-1997

| Month |

Support |

Self-Esteem |

Strategies |

| |

|

|

|

| August |

|

|

|

| September |

|

|

|

| October |

|

|

|

| November |

|

|

|

| January |

|

|

|

| February |

|

|

|

| March |

|

|

|

| April |

|

|

|

| Group Mean |

|

|

|

|

|

Qualitative

Analysis:

Presents findings

|

Overall group means for monthly meetings, ranging from

4.1 to 4.4, were high. This indicates that program participants

agreed that their needs for support, self-esteem, and

strategies were being met through the Graduate Mentoring

Program in Engineering.

Likewise, a summative survey (see Appendix E) was constructed

to examine the background, beliefs, feelings, and future

plans of program participants. Results of the 1997 survey

are contained in Appendix E. Some of the qualitative

and quantitative findings are included

below.

- Qualitative Responses:

- "I probably would have quit the Ph.D. program

without the peer support from others in the Graduate

Mentoring Program."

- "My [graduate] experience at Purdue has negatively

affected my self-esteem. The M&M Program has provided

me with positive support and often comments that

make me feel O.K. come from associates and friends

in the M&M Program."

- "My interactions with this group have helped

me a lot. I appreciate the time and effort that

staff members put in to make meetings successful.

I think the meetings seem professional and are

very productive and of great use to

participants."

- Quantitative Results:

- of MS program participants plan to continue

on for a Ph.D degree

- of Ph.D. program participants plan to pursue

academic careers

Further, the Graduate Mentoring Program received high

scores for providing beneficial meeting topics, using

meeting time well, and maintaining relationships between

program goals and monthly meeting topics. Participants

agreed that the mentoring program was a worthwhile experience

for them.

|

|

| |

Excerpt 5

[University of Washington]

|

|

Quantitative

Analysis:

Presents results of quantitative data analyses

(factor analyses)

|

Separate factor analyses were conducted on each of

the six hypothesized underlying constructs of prerequisite

conditions for success. The next section describes the

number of factors initially yielded for each of the

constructs (eigenvalues >1) and the percent of the total

variability explained by each construct.

Construct #1: COMMITMENT FROM THE

DEAN

| Factor 1 |

|

|

30.3% |

| |

Budget |

|

|

| |

Fundraising assistance |

|

|

| |

Dean evaluates program |

|

|

| Factor 2 |

|

|

24.4% |

| |

Study center |

|

|

| |

University-level programs |

|

|

| Factor 3 |

|

|

14.5% |

| |

Training through WEPAN |

|

|

| |

Salary paid by Dean/Provost |

|

|

| |

Dean evaluates program |

|

|

| |

|

Total variability: |

69.2% |

Factor analysis on this construct produced three factors,

that when taken together, explained 69.2% of the variability.

Each factor seems to make intuitive sense. Those institutions

with higher budgets tended to have: a) assistance with

fundraising; b) evaluations from the deans; c) study

centers; d) directors who received training from WEPAN;

and e) directors' salaries paid by the dean.

|

|

| |

Excerpt 6

[Northwest Indian College]

|

|

Quantitative

Analysis:

Displays quantitative data of primary student retention documents

|

Student Retention

A simple measure of student retention is the number of students who enroll and

complete credits each quarter. In the first quarter, 11 students enrolled, 13

enrolled for the second quarter, and 10 enrolled for the third quarter. One of the

students who left between the second and third quarter had severe health problems.

When these are addressed, he may return to the program. The other students who

failed to complete the third quarter are young males, one of which was a sporadic

member of the first TENRM cohort. The retention rate in the first year is 77% based

on 10 of the 13 recruits who actually enrolled in the first two quarters.

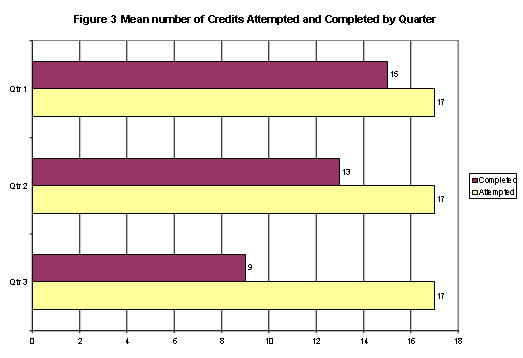

Student persistence is a measure of student effort. It takes in to account

the number of credits students attempt (register to take) compared to the number of

credits actually earned during the quarter. Persistence tends to drop as the quarters

progress. Figure 3 is a comparison of the mean number of credits attempted compared to

the mean number completed. The mean number of attempted credits for all three quarters

is 17, where as the mean number of completed credits is 15 for the first quarter, 13 for

the second quarter, and nine for the third quarter. Persistence also dropped as the

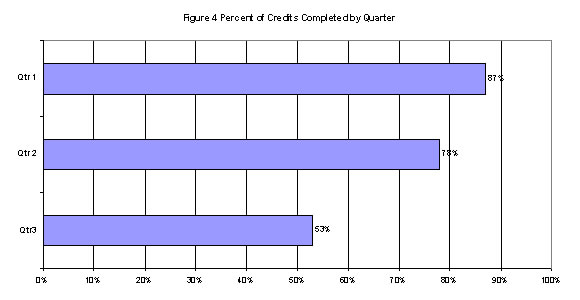

quarters progressed for TENRM I. The completion rate is illustrated in Figure 4. This

statistic is important in adjusting for quarterly GPA. Although the rate is just over

50% for the third quarter, some students needed to leave early to begin internships and

many students make up work over the summer months.

The five women who entered the program are doing well. All remained through all three

quarters and had slightly higher credit completion rates than the males. One of the males

who joined the program during second quarter did not complete the third quarter. One left

owing to illness. By the third quarter, women comprised slightly less than 50% of the cohort.

|

|

|

|

|

|