|

||

|

|

Key Topics |  |

|

Strategy |  |

Scenario |  |

|

Case Study |  |

|

|

References |  |

|

||||

|

Step 10: Use a consistent format and set of conventions to transcribe interview audiotapes. Make any necessary clarifications to the typed transcripts. Tally any quantitative data. Plan an approach to analyzing the qualitative data that is consistent with the evaluation purpose and questions. Making a Transcript. To consider and compare what participants say in their interviews, it is necessary to transcribe interview audiotapes. A typed interview transcript serves as a written record of every word spoken and thus is the most usable and "objective" form of the interview data. Relying only on interview notes for interview data analysis is much more problematic because of potential differences among interviewers in the thoroughness and accuracy of their note taking and because even the same interviewer may be inconsistent in the emphasis he or she accords to different topics in the interview. Although an interview transcript can be created in a variety of ways, there are several conventions we recommend:

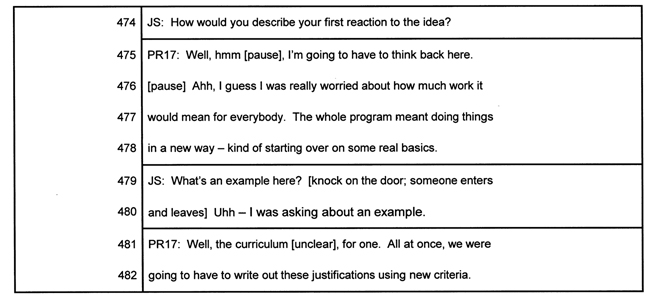

Here is an example of a transcript excerpt using the above conventions:

Generating good interview transcripts requires considerable resources. Transcribing is made easier by a transcribing machine, a tape player with foot pedal to allow hands-free typing. Professional transcription services are expensive, with estimates of $50 an hour being common. A 90-minute audiotape probably will take at least 6 hours to transcribe and yield approximately 50 pages. Transcription time will vary, depending on the quality of the equipment and the audio, the experience of the transcriber, and the complexity of the interview. If possible, have the transcription provided in the two-column format described above. After a tape is transcribed, it is critical that the interviewer read through it for accuracy. In particular, the interviewer should check that technical or specialized words were transcribed properly and try to fill in anything designated as unclear by the transcriber. Quantitative data from an interview should be tallied and coded for analysis (see Administering Questionnaires). Although the completeness of quantitative data can be an issue for questionnaires, this is less likely to be the case for interviews because the interviewer is present to elicit all answers. Analyzing Interview Transcripts. Many different approaches exist for analyzing the kinds of qualitative data yielded by interviews (see References). Although it is not possible to describe and explain all the major approaches here, it is useful to consider two distinct paths for analyzing interviews described by Seidman (1991): developing profiles and developing themes. Developing Profiles. The profile approach is appropriate when you want to take the totality of a participant's interview to tell a story through that participant's lens. Here, you want to consider how the elicited information and opinions fit together within the same interview to create a narrative that advances understanding. This approach fits best with less structured interviews because it is the unique experiences of each participant that guide the interview and the resulting profile. For example, a profile approach would make sense if you were studying the impact of a new media center and had just conducted open-ended interviews with a set of adult education students from greatly varying backgrounds. Because the learners differ significantly from one another in terms of native culture, language, and prior education, you anticipate that it makes sense to keep the experiences of each learner "intact" to tell a set of different stories. Here, your goal would be to illustrate the breadth of ways in which the media center affected learners' experiences by using these different stories and ultimately comparing and contrasting them at a more global level. In practical terms, creating a profile involves immersion in each interview as a separate entity. Go through the interview transcript and highlight the most useful and important text, noting the different topics being addressed. Eventually, your goal would be to write a narrative for each participant organized by key topics and using large chunks of unedited text. The organization of each profile might vary depending on the salient experiences of each individual. Developing Themes. The theme approach is called for when you want to look across different interviews to see how different participants' reactions compare on the same topic. From categorizing and comparing these different reactions, you strive to develop themes that can advance understanding. This approach fits best with more structured interviews in which all participants respond to the same, topic-specific set of questions. For example, assume you are evaluating the aforementioned media center, but that this time you have interviewed a set of high school sophomores, using the same specific questions. For each question, you are going to try to develop a set of categories that will capture the range of responses elicited by the question. To illustrate this approach, let's continue with the same example and assume this question has been asked in all interviews: "On a typical visit, how do you spend your time at the media center?" Your first step would involve pulling out all the text from each interview pertinent to this question and displaying the different responses in a format where they could be viewed together. You then would read through the responses several times, starting to develop and note potential categories (e.g., "a quiet place to study," "a place to use the computers," "a place to check out materials," "a place to meet friends"). Eventually, you would feel comfortable finalizing a set of categories and characterizing each participant's response in terms of the categories (note: some responses may fit into multiple categories, and an individual participant may represent a category uniquely). Once the major questions (or topics) have yielded sets of categories, it may be possible to look across these questions to identify patterns and common themes. |